Here’s a simple truth every author should know: your book is technically copyrighted the moment you write it down. But let’s be honest—relying on that automatic protection is like having a lock on your door but no key to actually use it. For any serious author, it’s a risk you can’t afford to take.

Copyright Basics: What Every Author Needs to Know First

It often surprises writers to hear that copyright is an inherent right. The second you save your manuscript as a document or print out the pages, it's legally yours. The law calls this being fixed in a "tangible medium," and it automatically establishes you as the owner from the moment of creation.

But this is where a critical distinction comes into play—the one that separates amateur-level protection from professional security. While you own the copyright automatically, you can't really enforce it in court without formally registering it with the U.S. Copyright Office.

Think of it this way: you might have the title to your car sitting in a drawer, but you can’t legally drive it or report it stolen without registering it with the DMV. Formal registration is the official, public declaration of your ownership, and it’s what gives your rights real power.

Why Formal Registration is Non-Negotiable

Registering your copyright takes your ownership from a passive fact and turns it into an active, legally enforceable right. It’s the key that unlocks the courthouse doors, giving you the legal standing to sue someone for infringement. Without it, you’re essentially left shouting into the void.

This is more important than ever. The global book publishing industry is a massive field, projected to hit $142.72 billion by 2025. With so much money and content floating around, just hoping no one steals your work is not a strategy.

To really see the difference, let’s quickly break down what you get with automatic copyright versus a registered one.

Automatic vs Registered Copyright at a Glance

This quick comparison table highlights the essential differences between the default copyright you get automatically and the powerful protection gained from formal registration.

| Feature | Automatic Copyright (Unregistered) | Registered Copyright (U.S. Copyright Office) |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Establishes you as the legal owner the moment the work is created. | Confirms and strengthens your ownership claim with an official certificate. |

| Public Record | No public record exists. Proof of ownership can be difficult. | Creates a searchable, public record of your ownership, deterring infringers. |

| Right to Sue | You cannot file a lawsuit for copyright infringement in a U.S. federal court. | A prerequisite to filing an infringement lawsuit. This is the biggest benefit. |

| Damages in Court | If you could sue, you'd be limited to proving and recovering only actual damages. | Eligible for statutory damages (up to $150,000 per work) and attorney's fees. |

| Presumption of Validity | No legal presumption; you must prove ownership and validity from scratch. | The court presumes your copyright is valid if registered within 5 years of publication. |

As you can see, the benefits of registration are what give copyright law its teeth.

The Real Power of Registration

Let's talk about those legal remedies for a second, because they're a game-changer.

- Public Record: Registration puts the world on notice that this work is yours. It’s a powerful deterrent.

- Legal Standing: Again, this is the most critical part. You simply can't sue for infringement in the U.S. without it.

- Statutory Damages: This is the big one. If you register before an infringement happens (or within three months of publication), you can claim statutory damages and have the infringer pay your attorney's fees. This means you could be awarded up to $150,000 per work without having to prove you lost a single dollar.

Without registration, you can only sue for "actual damages"—the money you can prove you lost because of the theft. That’s incredibly difficult and expensive to do. Statutory damages are the real hammer.

Understanding the Legal Ground You Stand On

Getting this right means understanding the basic rules that govern intellectual property. To truly protect your literary work, it's worth taking a moment to familiarize yourself with the fundamentals of Copyright Law. Knowing the difference between automatic rights and registered rights is the foundation for building and protecting your career as an author.

Getting Your Book Registered with the U.S. Copyright Office

Alright, let's move from the why to the how. The thought of registering your work with the U.S. Copyright Office can feel a little daunting, like you're about to wade into a sea of bureaucratic red tape. But I've been through it many times, and the truth is, it’s a surprisingly straightforward online process any author can handle.

Your main tool for this job is the electronic Copyright Office (eCO) online system. This portal is designed to make the whole thing accessible, and it’s a heck of a lot faster and cheaper than the old-school method of mailing in paper forms. You can expect to pay around $45-$65 to register a single book by a single author—a tiny investment for the powerful legal protection it gives you.

My goal here is to give you a real-world walkthrough, focusing on the specific steps you’ll take and the little details that can trip people up. We'll skip the legal jargon and get right to what you need to do to get it right the first time.

First Things First: Your eCO Account

Your journey starts at the official U.S. Copyright Office website. The first step is creating an eCO account, which is no different than signing up for any other website. Once you're in and looking at the dashboard, you'll see a few options.

The key is picking the right application. For your novel, memoir, nonfiction book, or poetry collection, you'll choose to register a Literary Work. It’s the catch-all for anything that's primarily text.

From there, the system walks you through a series of forms. It’s absolutely critical to be precise here. A simple typo or an incorrect date can cause delays or, in a worst-case scenario, create problems with your registration down the road.

A Quick Pro Tip on Timing: The absolute best time to register is within three months of your book's publication date. Getting it done in this window is called "timely registration," and it preserves your right to seek statutory damages and attorney’s fees if you ever have to sue for infringement. Trust me, that’s a massive advantage you don’t want to lose.

Nailing the Application Details

The application will ask for several key pieces of information. Let's break down the most important fields where I’ve seen authors get confused.

- Title of the Work: This needs to be exact. Enter the full title of your book, including the subtitle, precisely as it appears on your manuscript.

- Author Information: This is you! You must use your legal name here. If you write under a pen name, don't worry—there's a separate field where you can list your pseudonym. Just make sure you don't put your pen name in the legal name field.

- Copyright Claimant: For most self-published authors, the claimant is the same person as the author. The claimant is simply the legal owner of the copyright. The only time this might be different is if you’ve set up a business, like an LLC, to manage your publishing activities. In that case, you might list your LLC as the claimant.

Getting the author and claimant information right is the whole point. It creates a crystal-clear, official record of ownership.

Uploading Your Manuscript (The Deposit Copy)

This is probably the most crucial part of the whole process: submitting a "deposit copy" of your work. This is the official version of your book that the Copyright Office will keep on file as the definitive record of what you've protected.

Luckily, the eCO system makes this pretty simple by accepting common file formats.

- Accepted Formats: Stick with the basics. PDF, DOC, and DOCX are the most reliable choices. I always recommend using a clean, final PDF.

- File Naming: Keep it simple and clear. Something like "TheLostCity-Manuscript.pdf" works perfectly.

- Published vs. Unpublished: The system will ask if the work is published. If your book is already available for sale anywhere, it’s published. If not, it’s unpublished. It’s a simple but important distinction.

A common mistake I see is authors uploading an early draft full of typos, notes, or tracked changes. Don't do it. Always upload the final, polished version of the text. The copyright registration only covers the material you actually deposit.

And remember, copyrighting is just one piece of the puzzle. This process is completely separate from getting publishing identifiers. For instance, our guide on how to get an ISBN for my book covers another essential step you’ll need to take on your publishing journey.

Paying Up and Playing the Waiting Game

Once the forms are filled out and your manuscript is uploaded, you just have to pay the registration fee. The eCO system takes credit cards and direct bank transfers (ACH), so it’s quick and easy.

The moment you hit submit and pay, your copyright is technically considered registered as of that date. That’s the important part. But don't expect the official certificate to show up in your inbox the next day.

The government works at its own pace. According to the Copyright Office, the average processing time for an electronic application is currently around 2-3 months, though it can sometimes stretch longer if they're swamped. You can log into your eCO account to check the status, but honestly, the best approach is to be patient. Eventually, a formal certificate of registration will arrive in the mail—a very important piece of paper you should file away somewhere safe.

While copyright protects your actual writing, serious authors often look at other ways to protect their brand. For instance, you might also want to learn how to register a trademark for your series title or author name. That’s a separate legal tool, but it’s a smart move if you're building a long-term author career.

How to Navigate International Copyright Protection

Once your book is out there, it's not just available in your home country—it's global. In an instant, someone in Tokyo can be reading the same words as someone in Texas. This brings up a big question I hear all the time: "How do I copyright my book internationally?"

The good news is, you don't have to file paperwork in every single country. Most of the heavy lifting is already done for you, thanks to some key international agreements.

The most important one is the Berne Convention, a treaty signed by over 180 countries. Think of it as a global handshake. The core idea is "national treatment," meaning if your book is copyrighted here in the U.S., every other member country agrees to protect it just as they would one of their own.

So, that U.S. copyright registration becomes your golden ticket. The moment it's official, you've automatically established foundational rights in places like the UK, Australia, Japan, and most of Europe without lifting another finger.

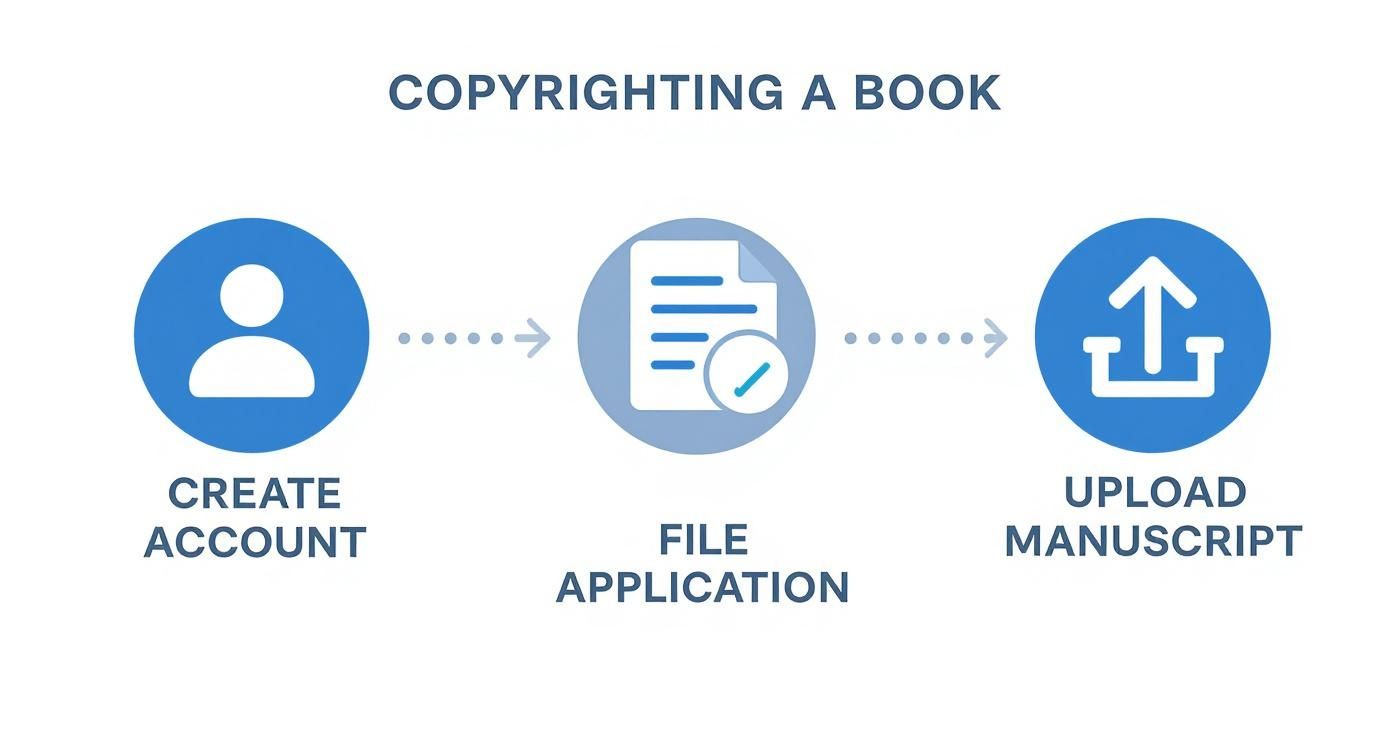

Securing that initial U.S. copyright is the cornerstone of your entire international strategy. The process is pretty straightforward.

This three-part process—getting an account, filing the application, and uploading your manuscript—is what unlocks both your domestic protection and that widespread international recognition.

When Automatic Protection Isn't Enough

While the Berne Convention is a fantastic safety net, it's not a silver bullet. Relying only on the treaty can leave you in a tough spot if you actually have to defend your rights abroad. The truth is, enforcing your copyright in a foreign country can get complicated and costly if all you have is a U.S. registration.

Let's play out a scenario. Imagine a publisher in Germany releases an unauthorized translation of your new thriller. The Berne Convention gives you the right to sue them, but the legal battle will happen on their turf, in the German court system. Having a German copyright registration in hand would make that whole process faster, cheaper, and give you a much stronger position from the start.

My advice? Think of your U.S. registration as your global copyright passport. It gets you in the door. But a local registration in a key market is like having a local lawyer on speed dial—it makes everything so much easier if trouble starts.

This is especially critical in major markets where your book is likely to sell well and where infringement is more common. The six largest book markets—the United States, China, Germany, Japan, France, and the UK—account for more than 60% of the estimated €114 billion spent on books worldwide. If you want to dig deeper, you can check out more on global publishing statistics and market trends.

Practical Steps for Global Copyright Defense

So, what can you do to shore up your book's protection for a global audience? It really comes down to a few smart, proactive moves.

1. Craft a Strong Copyright Notice

That copyright page in your book is prime real estate—use it. A clear, internationally understood notice is your first line of defense. It should always include:

- The copyright symbol © (or the word "Copyright")

- The year of first publication

- Your full legal name (or your publishing company's name)

- A firm rights reservation statement, like "All rights reserved."

Here’s a solid example you can adapt: © 2025 Jane Doe. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

2. Consider Local Registration in Key Markets

If you're planning a big launch in a specific country or you're licensing out translation rights, it's worth the investment to register your copyright locally. I particularly recommend this for:

- High-risk markets: Countries where piracy is a known problem.

- Major translation markets: If a foreign publisher is putting serious money into your work, local registration protects both of you.

- Complex legal systems: In some countries, a local registration gives you a clear and undeniable advantage in court.

Getting a handle on the nuances of global book publishing is a must for any author with big ambitions. Your U.S. registration is always your most important asset, but being strategic about where you add extra layers of protection can save you a world of headaches down the road.

Common Copyright Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Navigating the copyright process is a huge win for protecting your book, but a few subtle missteps can cause major headaches down the road. I've seen countless authors make small errors that jeopardize their legal standing, and they're almost always avoidable. Let's walk through the most common pitfalls so you can get it right the first time.

The Premature Registration Problem

One of the most frequent mistakes is jumping the gun and registering a manuscript that isn't really finished. It’s so tempting to file the moment you type "The End," but this can backfire.

Your copyright registration protects the exact version of the work you deposit. If you later do a major rewrite, add a few chapters, or completely change the ending, none of that new material is covered by the original registration. You'd have to file a whole new application for a "derivative work," which costs more time and money.

Think of it as a snapshot in time. You want that picture to be of the final, polished product. Minor typo corrections are fine, but anything substantial isn't covered.

How to avoid it: Just wait. Don’t register until your manuscript has been through final edits and proofreading. The copy you upload to the Copyright Office should be the definitive version of the book you’re about to publish. A little patience here ensures one registration gives you the broadest possible protection.

Author vs. Claimant: Who Owns What?

Another common tripwire is mixing up the "author" and "claimant" fields on the application. They sound similar, but confusing them creates a messy paper trail that’s a real pain to fix later.

The distinction is simple but absolutely critical, especially if you use a pen name or have a business entity like an LLC.

- The Author: This is always the human being who wrote the words. The U.S. Copyright Office wants your legal name here, no exceptions.

- The Claimant: This is the person or entity who legally owns the copyright. For most indie authors, the author and claimant are the same.

The confusion starts when things get more complex.

Let’s say you write under a pseudonym and have also set up "Awesome Books LLC" for your business. In this scenario, your legal name goes in the "Author" field, "Awesome Books LLC" goes in the "Claimant" field, and your pen name goes in the "Pseudonym" field. Getting this wrong can seriously muddy the chain of ownership.

How to avoid it: Before you even start the application, get clear on your legal structure. If you’re a sole author publishing under your real name, you are both the author and the claimant. If you use an LLC or a pen name, take a moment to double-check that you're putting the right information in the right box on the eCO form.

Misunderstanding Third-Party Content

This is probably the most dangerous mistake: improperly using content you didn't create yourself. Authors often want to include song lyrics, famous quotes, or images, assuming it’s covered by "fair use." That’s a very risky assumption.

Fair use is a complicated and highly subjective legal defense, not a blanket permission slip. Weaving a few lines from a hit song or a copyrighted photo into your book without explicit, written permission can put your entire work at risk of an infringement lawsuit. Seriously. The owner of that tiny piece of content could demand you pulp your books and sue you for damages.

How to avoid it: When in doubt, leave it out—or get written permission.

- Song Lyrics: Just assume all lyrics are protected. Licensing them can be incredibly expensive and time-consuming. It’s almost always better to describe the feeling of a song or invent your own lyrics.

- Images & Artwork: Only use images you created yourself, are clearly in the public domain, or for which you have purchased a specific commercial license.

- Extended Quotes: While quoting for review or commentary is often fine, lifting large blocks of text from another author's book is not.

Avoiding these mistakes isn't about being a legal eagle; it's about being a careful and professional author. Taking a few extra minutes to confirm your manuscript is final, clarify ownership, and secure permissions ensures your copyright registration is the solid shield it's meant to be.

Do You Need to Handle Copyright Yourself?

Taking the DIY route to register your copyright is perfectly fine—and it’s the most affordable way to do it. But let's be honest, for many authors, staring down government forms and legal portals is the last thing you want to do after pouring your soul into a manuscript.

The good news? You don't always have to go it alone.

If you’ve landed a traditional publishing deal, you can probably breathe a sigh of relief. Most publishers will handle the entire copyright registration for you, usually at their own expense. For them, it’s just part of protecting their investment in your book.

A quick word of caution, though. In the flurry of publication, things can get missed. I’ve seen cases where a publisher simply forgot to file the paperwork. So, it’s always a good idea to circle back a few months after your book is out and double-check the public U.S. Copyright Office database. A little due diligence goes a long way.

Outsourcing Copyright for Indie Authors

What if you're self-publishing but would rather not tangle with the registration process yourself? You can absolutely outsource it. There are plenty of companies and specialized legal services that will manage the whole application for you, from navigating the forms to submitting your manuscript deposit.

Of course, this convenience has a price tag. The government filing fee itself is pretty reasonable, usually between $45 and $65. A third-party service will tack on its own fee, which can run anywhere from $100 to over $300. You're essentially paying for their expertise and your own time back.

- Pros: It saves you time, eliminates the stress of getting the application wrong, and gives you solid peace of mind.

- Cons: It costs significantly more than just doing it yourself.

Is it worth it? That’s a call only you can make. If you’re juggling multiple projects and the registration feels like a major roadblock, then hiring help might be a fantastic investment.

Clearing Up Common Publishing Confusions

When you're new to publishing, it’s easy to get copyright tangled up with all the other official-looking numbers your book needs. Let's clear up a couple of the most common points of confusion.

Key Takeaway: An ISBN, ASIN, or LCCN is a product identifier for commerce and cataloging. It is not a substitute for copyright registration and offers zero legal protection against infringement.

An International Standard Book Number (ISBN) is just your book's product barcode. Booksellers, libraries, and distributors all use it to track inventory. You absolutely need one to sell your book through most retailers, but it has no bearing on who actually owns the creative work.

Likewise, a Library of Congress Control Number (LCCN) is simply a serial number the Library of Congress assigns to help catalog books. It's a great tool for getting your book into the library system, but it provides no copyright protection whatsoever.

Ultimately, your publishing path plays a huge role in how you'll manage tasks like copyright registration. Understanding the nuances between different approaches is key. You can dig deeper into the pros and cons of traditional vs. self-publishing to see which model truly aligns with your goals. No matter which path you choose, securing your copyright is non-negotiable—the only real question is whether you’ll file it yourself or let a trusted partner handle it for you.

Frequently Asked Questions About Copyrighting a Book

Let's dig into some of the questions that pop up most often when authors start thinking about copyright. After walking hundreds of writers through this, I've noticed a few common sticking points. Here are the clear, straightforward answers you need.

How Much Does It Cost to Copyright a Book?

The good news is that securing your rights won't break the bank. Right now, filing a copyright for a single literary work by a single author through the official U.S. Copyright Office online portal usually costs between $45 and $65.

Of course, these government fees can change over time. It's always a good habit to pop over to the official website and check their current fee schedule before you start the process. Honestly, for the peace of mind it provides, this is one of the best small investments you can make in your author career.

Can I Copyright a Book Idea?

This is a big one, and it trips up a lot of new writers. The short answer is no, you can't copyright an idea. Copyright law protects the tangible expression of an idea, not the abstract concept itself.

So, your brilliant idea for a time-traveling detective who solves cold cases? Not protectable. The unique plot twist you came up with in the shower? Also not protectable.

What is protected is the actual manuscript you write—the specific words, sentences, and chapters you use to bring that idea to life. That's the "expression" the law is designed to shield.

Key Takeaway: You can't own the concept of a wizarding school, but you can own the specific 7-book series you write about it. It’s a crucial distinction in the world of intellectual property.

How Long Does Copyright Protection Last?

Fortunately, copyright is built for the long haul. For any book written by an individual author on or after January 1, 1978, the protection lasts for the entire life of the author, plus an additional 70 years.

This long-term protection is fantastic because it means your literary legacy is secure. Your work can continue to earn income for your family and your estate long after you've written "The End."

Do I Need a New Copyright for a Revised Edition?

The classic "it depends" answer applies here, but it's pretty simple. If you're just fixing a few typos or correcting minor grammatical goofs, you don't need to file for a new copyright. Your original registration still covers the book.

However, you absolutely should register the new version as a derivative work if you've made significant, substantial changes. This would include things like:

- Adding brand-new chapters

- Rewriting large sections of the manuscript

- Including a new foreword, illustrations, or appendices

Registering the revised edition protects all that new material. It ensures your entire updated book is legally buttoned up and shielded from infringement.

Protecting your work is a critical step, but it's just one piece of the publishing puzzle. If you want a partner to handle everything from copyright registration to global distribution, the team at BarkerBooks is ready to help. Discover our full suite of author services and start your publishing journey today at https://barkerbooks.com.